Machiavellian Markets Discipline

The European debt crisis of 2011–2012 laid bare the market’s ability to humble everyone.

It’s a common assumption that investors’ perception of a country’s economic risk can be accurately tracked through the movements of its primary stock index. There is some truth to this idea. Equity markets offer a real-time snapshot of investor sentiment, reacting swiftly to news, uncertainty, or exuberance. When the DAX plunges, or the S&P500 sells off sharply, the market is clearly saying something. But what, exactly, is it saying? The problem is that equity prices, taken in aggregate, are often noisy. They respond to emotion as much as to fundamentals, frequently driven by narratives, liquidity surges, and positioning rather than long-term shifts in macroeconomic stability. A 15% drop in equities might look catastrophic, until it’s fully reversed within a week. How, then, do we meaningfully interpret the signal within the volatility? What does a rally really say? What does a crash truly warn us about?

When it comes to systemic, macroeconomic, or fiscal risk, issues that affect the structural integrity of an entire national economy, the best signals often come from somewhere else entirely. From markets that move slowly, require scale, and are deeply rooted in economic fundamentals.

Among these, the sovereign debt of developed nations stands out. It is the largest and most structurally important asset class in the world. And when it shifts, when yields climb persistently or spreads widen significantly, it's not the result of speculative noise or a temporary narrative swing. It’s the visible trace of deliberate, weighty reallocations by the most consequential actors in global finance: central banks, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, insurance giants, and global macro managers. These moves are slow, but they are meaningful. And when they gather momentum, they carry a force that’s difficult to stop.

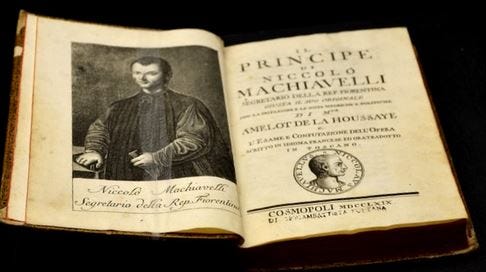

The European sovereign debt crisis of 2011–2012 remains perhaps the clearest case study about the formidable power of markets to discipline the “Prince”, in the Machiavellian sense.

Yield spreads weren’t just market data points; they became tools of discipline. In those years, markets had the power to force the hand of entire governments. They didn’t just react; they called for clear and sustainable actions.

It didn’t matter how large a country’s GDP was, how modern its institutions, how strong its military, or how charismatic its leadership. If the market’s confidence was lost, the consequences were immediate and brutal. Anyone with a deep understanding of capital flows knows what it means when sovereign yields begin to move outside historical ranges. It’s the moment when people behind the scenes start to worry, seriously.

Unwinding a major allocation to sovereign debt is a long and painful process. If it begins without care, it can quickly spiral. Policymakers fear this scenario more than almost any other. The process should never begin: and if it does, it must be managed with extreme caution. Because once global markets begin to turn their gaze toward an issuer with skepticism, the chain reaction that follows is often unstoppable.

We’ve seen this play out time and again. Countries with robust, even booming economies, members of the global elite, have discovered too late how hard it is to push the genie back into the bottle. Argentina, once an economic powerhouse, has spent decades trapped in cycles of default. In Europe, the so-called “peripheral” economies required eight to thirteen years to regain a measure of trust from international investors; and the path back involved austerity, internal deflation, and real social pain. France, today, walks a tightrope with nothing but air below. The UK, in 2022, received a sharp and unmistakable warning when its gilt market turned against it overnight.

These are not abstract concerns. They are warnings written in bond yields and sovereign spreads. signals that should not be ignored.

Every policymaker would be wise to keep a watchful eye on a handful of key indicators; signals that, in increasing order of importance and informational depth, can offer a sobering glimpse into the market’s judgment:

First comes the spread against a risk-free benchmark: often dismissed as noise, but historically a reliable early warning.

Then, the volatility of long-dated sovereign yields: a tremor here speaks to deep uncertainty about a country’s fiscal trajectory.

Most telling of all is the slope of the yield curve (once stripped of the distorting effects of short-term monetary policy expectations). It reflects the market’s truest belief about future growth, inflation, and, ultimately, trust.

In the coming essays, I’ll explore some of these themes through detailed case studies. Because what seems distant today may, in hindsight, become the lesson everyone wished they had learned just a little earlier.